By Anum Khan

Consumers in the Arab world have long pursued and coveted some of the finest designers and brands in the fashion world. Accustomed to buying American or European brand names, many avid shoppers go as far as to travel to cities across Europe in search of high fashion labels and quality.

These consumers, however, often overlook local Arab designers who have also been producing some of the most lavish works and designs in the region.

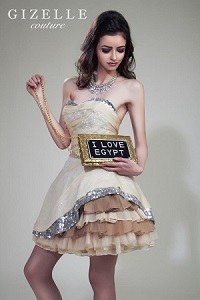

Gizelle Begler an Egyptian-American fashion designer based in Cairo, Egypt, tells Elan Magazine that purchasing foreign name brands in the Middle East says a lot about one’s status.

“One little logo on a bag sends a message strong enough that consumers feel it’s worth the overpriced purchase,” said Begler.

The total buying power of the Middle East, or gross domestic product, amounts to about $2 trillion, most of which comes from the six Gulf countries. These countries also boast $6,000 per capita, which is bigger than that in China or India. Dubai was also ranked as the second-most important destination for international retailers after London, according to a study by real estate services firm CBRA.

The Arab market is vibrant and the potential and power of Arab consumers is enormous. Still, Arab businesses fail to benefit from this enviable spending power.

Working towards her own locally global vision, PR expert Rozan Ahmed created bougi.com – a movement dedicated to championing creative people, works and projects from “returning markets” such as the Middle East and Africa. She also advocates the concept of “cultural ownership” which she defines as “knowing who you are and being proud of who you are and assembling your message of sale.”

Ahmed says that the psychology behind local consumer preference for American or European brands stems from the “acceptance—for what is dominant,” and is a “result of colonialization and cultural saturation.”

She explains that there is a “worship of the West” where Western brands are “projected into our brains everyday,” through ubiquitous advertising and marketing campaigns. When consumers enter Dubai Mall, for example, they immediately recognize and therefore buy more dominant brands like Chanel and Louis Vuitton, rather than opt for local brands that may be just as luxurious, if not more.

Gamila Mostafa, a resident of Egypt, says that when she shops locally she notices how “people feel the need to buy European brands for the name and to be accepted by society.” Mostafa also points out that the phenomenon is often seen in the upper middle class to upper class where certain brand “names build social levels—but that’s all psychological.”

Quality also seems to play a role in consumers’ preference for Western brands as opposed to locally made products. Gamila says she prefers purchasing Italian brands because the quality is better than Egyptian brands.

“The biggest challenge for high end Arab designers [is] breaking in and making a name for yourself that is associated with prestige and quality,” said Begler. “Designers need to provide a consistent level of quality.”

Begler explains that American and European brands are often “favored because they provide a reliable and consistent level of quality that is not always guaranteed in local Egyptian products.” Still, Arab brands that do have exceptional quality, but they often go unnoticed because they are not associated with trendy Western brands.

Consumers tend to gravitate toward brands and items that are in style that can create, maintain or raise their social status. Local media and fashion-related industries play an instrumental role in molding and shaping this mindset.

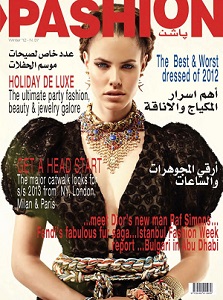

It is also not entirely a consumer’s fault for buying Western brands. Local magazines like Pashion, eniGma and Fusta

Ahmed says there is a “lack of ownership of voice,” where dominating magazines are often “poor Arab versions of Western titles” run by foreigners.“How does one take pride in cultural ownership if the voice is foreign?” asks Ahmed. In general, she states that consumers need to ask themselves – “Who is influencing me? Who is talking to me? Do I want my local economy to change? How does one take pride in cultural ownership if the voice is foreign?”

When there is a better management and ownership of voice, consumers will change the way they buy. But first, Ahmed says, “We need to stop flying in international experts to tell us how we shop. We know what ‘Made in Paris’ or ‘Made in Tokyo’ means. We need to understand what ‘Made in the Middle East’ means,” and take ownership of that.

What does “Made in the Middle East’ mean to you? Send us your answers (@elanthemag) using hashtag #locallyglobalMiddleEast

Comments