Some people call Dharavi an eyesore in the middle of India’s financial capital, Mumbai. Its residents call it home.

Even today, the Sion – Mahim entrance into Dharavi draws a desperate and almost imploding impression. Communal sanitations, narrow lanes, and dirty streets punctuate whatever spaces are not occupied by the slum dwellers. Teeming with over one million plus souls, the 217 hectare sprawl is one of the most densely populated places on the planet with as many as 18,000 inhabitants sharing 1 acre.

An illegal settlement, Dharavi is deprived of public services and utilities and yet, people have called it home for three to four generations now. Dharavi is deservedly Asia’s largest slum.

When Danny Boyle portrayed the Dharavi underworld in his Oscar-winning opus “Slumdog Millionaire,” cinema goers around the world realized that an Indian version of the Brazilian favelas does exist. The hardships, poverty and shanty living conditions he artistically captured in his piece personified the very soul and will power of its residents. With the controversial slum tourism dilemma on the rise, a guided tour through the slums has been seen as demeaning and frowned upon. But the financials and hard work of the Dharavi slum-dwellers is paradoxically inspirational.

With over 10,000 different businesses operating within the rundown sprawl, the entrepreneurial setups generate a whopping 30 billion rupees ($559 million) in annual revenues. Household businesses and entrepreneurial businesses employ the Dharavi residents to work in tanneries, leather factories, potteries and textile mills; outputs of which are sold across India and internationally. A wealth of talent and a lot of wealth is what Dharavi is, and rightly so, Prince Charles cited Dharavi as a role model for sustainable living back in 2010.

Organized by the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA), the Dharavi Biennale, a fascinating three-week festival, showcases the talent and art that the residents of Dharavi have to offer while informing people about the health, social and recycling issues they face as well.

Organized by the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action (SNEHA), the Dharavi Biennale, a fascinating three-week festival, showcases the talent and art that the residents of Dharavi have to offer while informing people about the health, social and recycling issues they face as well.

According to a press release from SNEHA, the biennale invites residents of Dharavi to “meet, educate themselves on urban health, learn new skills, and produce locally resonant artworks that are authentic, honest and relevant.” By showcasing the various installation and performance art creations, the residents have the opportunity to reflect and draw the attention of visitors to issues prevalent in Dharavi.

“What we see is that Dharavi is sitting on a lot of wealth and a lot of talent and art that gets missed out when you want to show squalor and slum,” said festival co-director Nayreen Daruwalla.

Showcasing Dharavi to the World

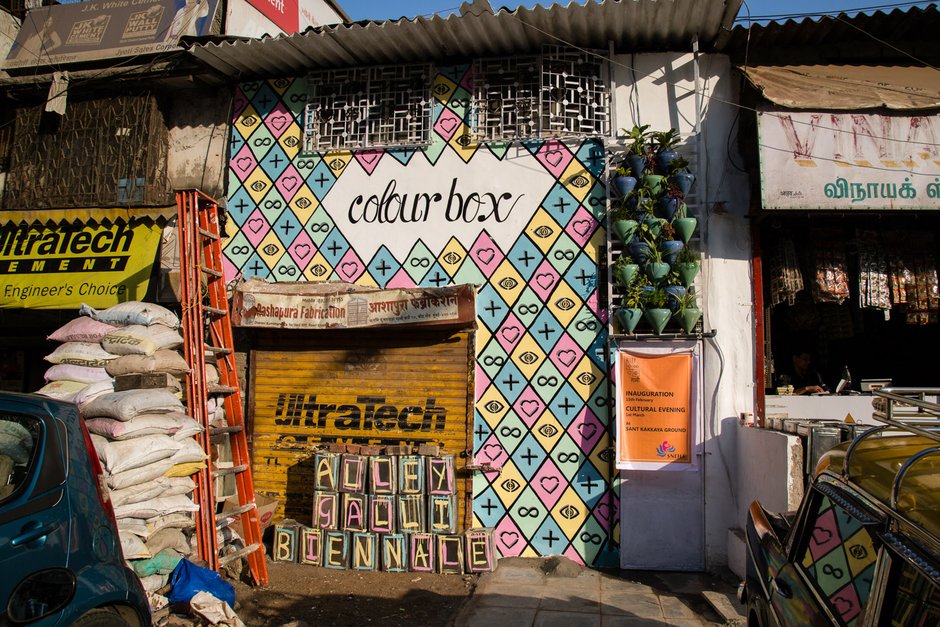

The show titled “Alley Galli Biennale” (galli means narrow lane in Hindi) allows local artists, along with support from their mentors, to create eclectic and unique pieces of art from raw materials sourced from in and around Dharavi as well as informative performances by its residents.

‘Hope and Hazard’ for instance, was a stunning arrangement of used oil tins and cans that reflected the hardships and perils that dwellers faced on a daily basis. Similarly, one of the Dharavi businesses that involved the cleaning and disinfecting of surgical vials for pharmaceutical companies, was captured in a sculpture titled ‘Still Life’ which portrayed a pregnant woman composed entirely from the same vials. Since the inception of the biennale, residents such as Dilip Thawal, who would otherwise never have the means to rent a gallery, can now work with established artists and mentors to create art that resonates the social issues at hand which, according to artist Nalini Malani, makes “the invisible visible.”

‘Hope and Hazard’ for instance, was a stunning arrangement of used oil tins and cans that reflected the hardships and perils that dwellers faced on a daily basis. Similarly, one of the Dharavi businesses that involved the cleaning and disinfecting of surgical vials for pharmaceutical companies, was captured in a sculpture titled ‘Still Life’ which portrayed a pregnant woman composed entirely from the same vials. Since the inception of the biennale, residents such as Dilip Thawal, who would otherwise never have the means to rent a gallery, can now work with established artists and mentors to create art that resonates the social issues at hand which, according to artist Nalini Malani, makes “the invisible visible.”

The objective of the biennale is to showcase the abundance of talent in Dharavi whilst ignoring the obvious squalor and destitute conditions of the ‘illegal’ residences. But that does not mean the issues of Dharavi are neglected.

‘Map the Hurt’ was a hand-embroidered quilt depicting the troubled regions where women were subjected to domestic abuse. With resources limited to recycled materials, local produce and even disposed garbage, art would be seemingly difficult to create but the sheer talent and determination of the Dharavi spirit knows no boundary.

‘Map the Hurt’ was a hand-embroidered quilt depicting the troubled regions where women were subjected to domestic abuse. With resources limited to recycled materials, local produce and even disposed garbage, art would be seemingly difficult to create but the sheer talent and determination of the Dharavi spirit knows no boundary.

Color Box – Creating a different perspective

For a meager $11, slum tourism provides visitors the disdain opportunity to witness life in the slum first-hand whilst trolling along the alleys. Peeking into homes as they walk along, some visitors are consumed with awe at the raw determination and quality of life the residents strive to earn for themselves. But more often than not, it is the desolate look in a child’s eye or the queues at the communal bathroom that provide the destitute touch.

The Dharavi Biennale aims to do exactly the opposite. Resident artists from the region get a chance to mingle with professionals and hone their skills which are then put to good use. Shadowing the harsh realities of slum life, art is used instead to portray and depict unspoken incidents and events. Situated on an arterial road in the alleyways, the Color Box is the headquartered center of the biennale where various events, aptly termed Art Box, showcase the produce of the local community.

Resident artists from the region get a chance to mingle with professionals and hone their skills which are then put to good use. Shadowing the harsh realities of slum life, art is used instead to portray and depict unspoken incidents and events. Situated on an arterial road in the alleyways, the Color Box is the headquartered center of the biennale where various events, aptly termed Art Box, showcase the produce of the local community.

The entrepreneurial spirit and multi-million dollar revenue engine of Dharavi would never have been if not for their unfortunate living conditions. SNEHA, with the Dharavi Biennale concept, have changed that today and slum tourism is no longer about staring in through the broken windows of its residents’ homes.

“People think this is just a slum area where we aren’t educated, but the truth is that it’s a place where so many talents come together,” said 21-year-old student Saraswati Bandare, who helped create giant puppets for the biennale’s opening show about tubercolosis. “We’re proud to be from Dharavi.”

Amazing to see, wonderful to hear about.